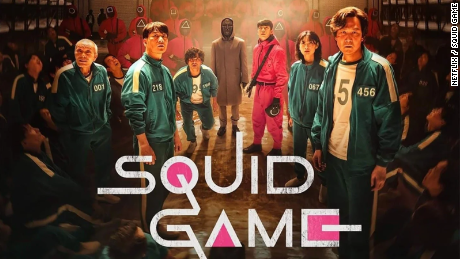

Hundreds of cash-strapped contestants accept an invitation to compete in children’s games for a tempting prize, but the stakes are deadly.

HONG KONG — Why are South Koreans watching “Squid Game”? Because everyone else is.

The nine-episode horror series on Netflix has hit No. 1 in 90 of the streaming service’s markets around the world, including South Korea, where it was made.

“I got to the point where I could not hold a conversation without watching the show,” said Jung Dunn, a security analyst in Seoul, the South Korean capital.

But the show also strikes a nerve because it unflinchingly addresses a problem that is particularly entrenched in South Korea: debt and the never-ending struggle to pay it off.

The cast of “Squid Game” features some of South Korea’s biggest stars, including Lee Jung-jae as the protagonist, Seong Gi-hun, a hopelessly indebted father who receives a business card from a stranger offering him a way out. Along with 455 other contestants — from all walks of life but all deeply in debt too — he agrees to compete for a cash prize of 45.6 billion won (about $38 million) by playing a series of traditional Korean children’s games, only to discover that elimination from each round means death.

“There’s this dissonance between Korean pride that this Korean show is dominating Netflix all around the world, and the discomfort with what the show appears to expose about Korea,” said CedarBough Saeji, an assistant professor of Korean and East Asian studies at Pusan National University in Busan, South Korea. “Koreans love to be No. 1, but No. 1 at the cost of kind of airing your dirty laundry is a somewhat different thing.”

That South Korea also produced “Parasite,” the 2020 Oscar winner for best picture that also focused on themes of inequality, has probably accentuated this discomfort, Saeji said.

Still, “Squid Game” is wildly popular in its home country.

The show was released on Sept. 17 just before Chuseok, a Korean holiday similar to Thanksgiving when families gather, the perfect time for binge-watching. The surge in network traffic led one internet service provider to sue Netflix to cover its costs.

The fervor has also spilled over into real life. A street vendor in Seoul who provided the makers of “Squid Game” with dalgona, a brittle sugar candy at the center of one of the games, told Reuters that he had seen a boom in business.

Thousands of curious South Koreans also tried the eight-digit phone number that appears on the business card, which the show’s makers didn’t realize would reach an actual person. The owner of the number, and even people with similar numbers, have been inundated with calls and messages at all hours.

On Wednesday, Netflix said it was working with the show’s local production company to address the issue, including editing scenes to remove the number.

Park Sae-ha, a senior studying economics at Yonsei University in Seoul, said “Squid Game” was “spell-binding because it was so explicit and blunt.”

“Although I am young, I could easily relate to the hard reality of a very competitive society,” she said.

That intense competitiveness may be one reason South Korea has been so successful, with a period of rapid industrialization starting in the 1960s that turned it into the world’s 10th-largest economy. But as in many other countries, a university degree and a white-collar job don’t guarantee the financial security they used to, Saeji said. With an average income of about $42,000 a year, many Koreans now find they have to borrow to keep up.

Fueled by low interest rates, household debt in South Korea has grown significantly in recent years, and is now equal to the country’s annual GDP. (In the U.S., by contrast, household debt is about 80 percent of GDP.) People may rack up debt because of credit card spending, unemployment or gambling losses, but a large chunk of it is tied to real estate.

Housing prices have been rising fast, especially under President Moon Jae-in, and the average price of an apartment in Seoul is nearing $1 million. Lending curbs and efforts to cool the housing market have done little to rein in household borrowing. In addition to housing, some Koreans, especially young people, borrow money to invest in cryptocurrency.

Many Koreans start out by borrowing from legitimate financial institutions like banks, said Koo Se-Woong, a commentator on Korean culture based in Germany. When that avenue is exhausted, they may move on to second-tier lenders that charge higher interest.

In the worst-case scenarios, he said, borrowers turn to loan shark operations that can charge triple-digit interest rates, “and then you are pushed into situations from which you really cannot get out.”

According to some estimates, there are 400,000 Koreans in debt to loan sharks.

“When you look at the characters in the show who are participating in this game, they represent that demographic of the Koreans who are in the worst possible situation because of their personal debt,” Koo said.